Wagons Ho! : The McLane Factory

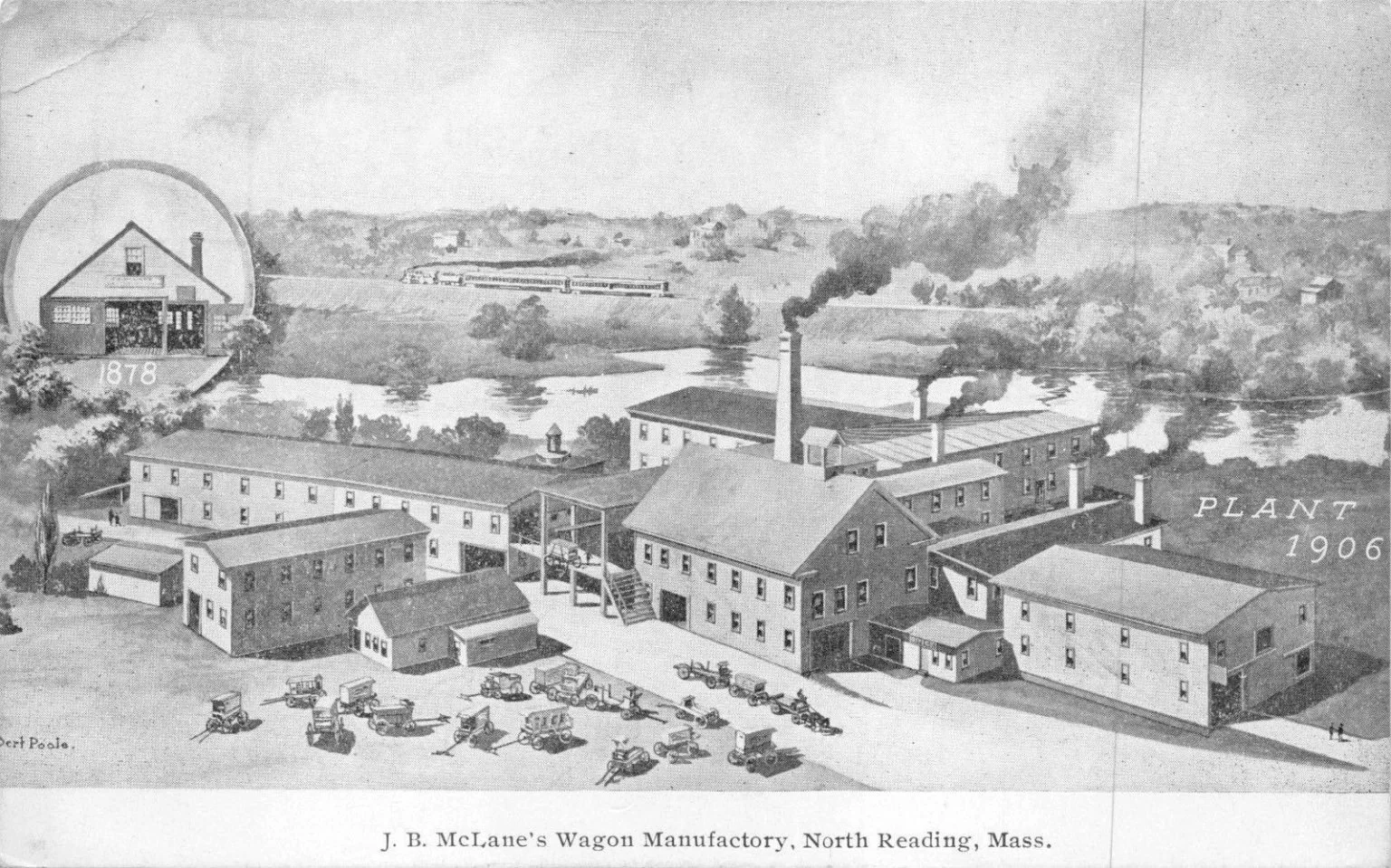

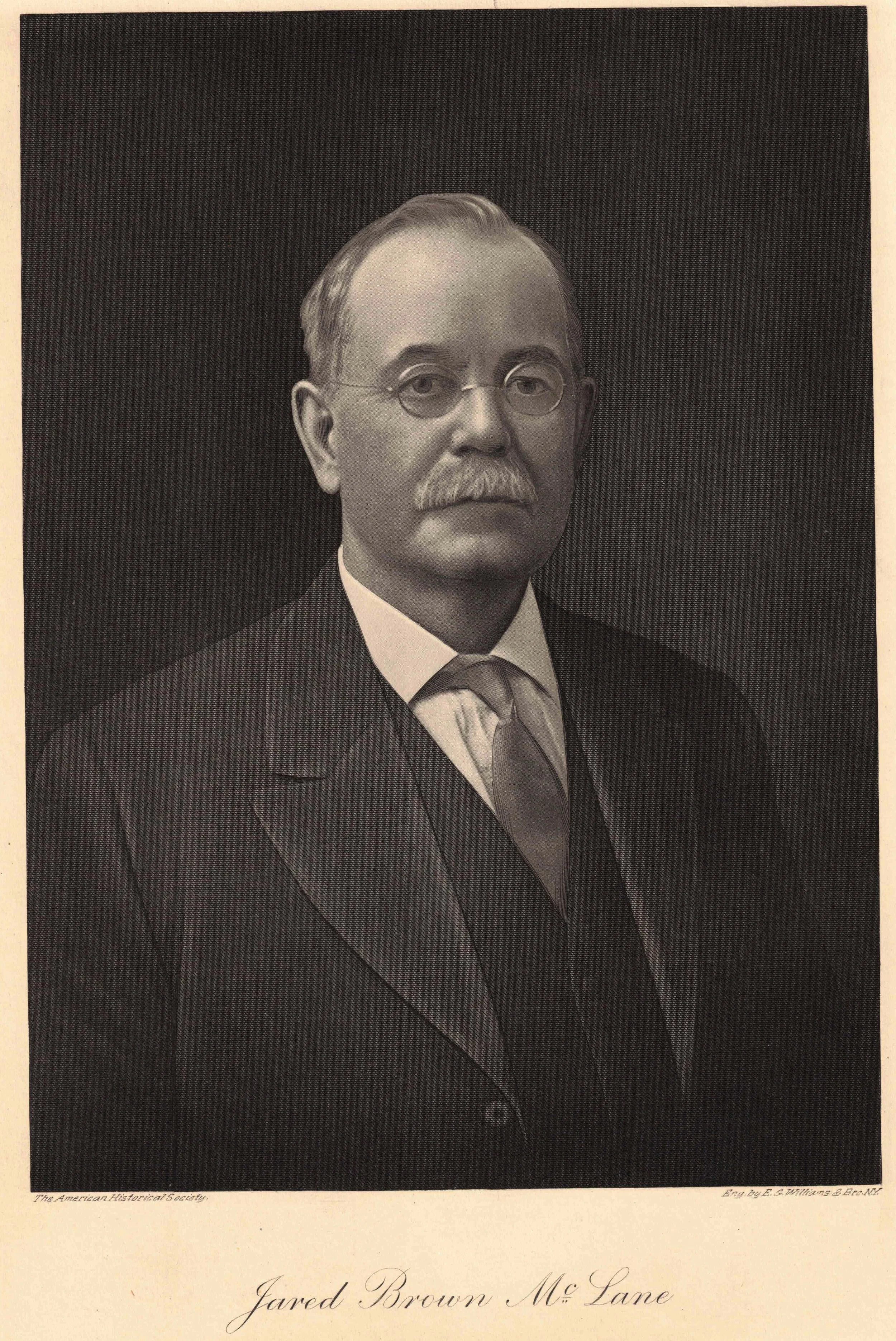

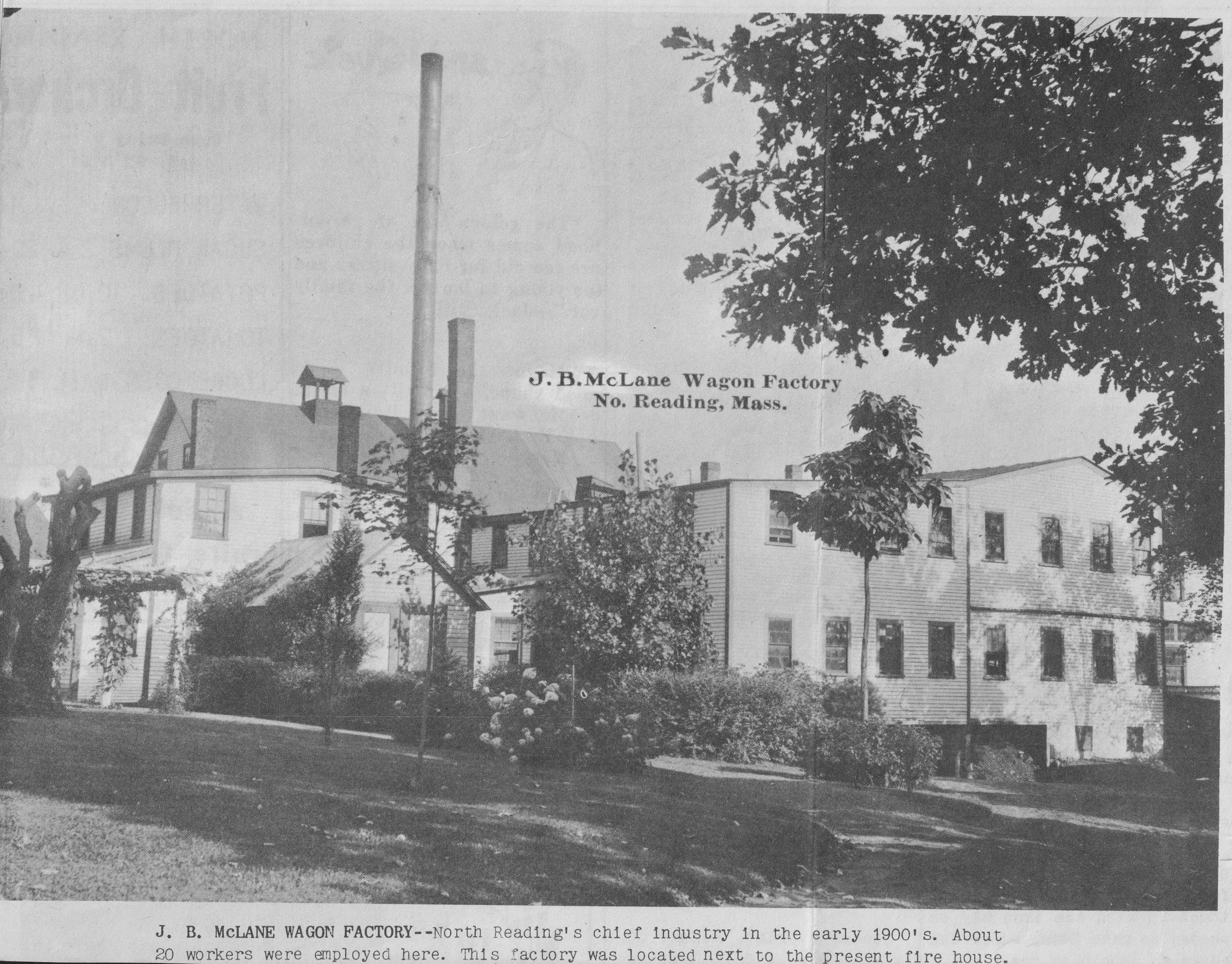

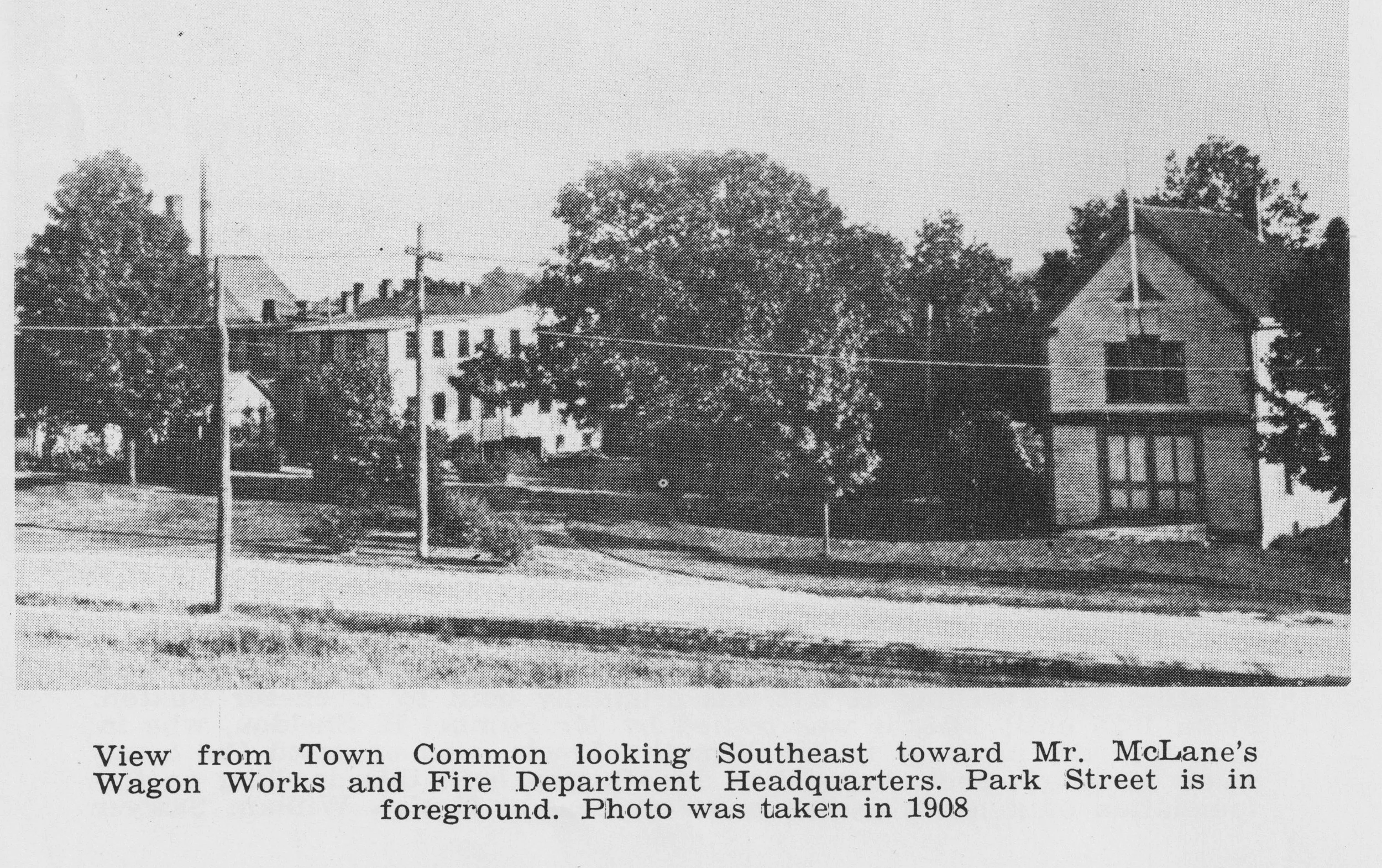

If you lived in North Reading in 1900, you would know—and might even work for—Jared McLane, one of the most important wagon makers in the United States. From his sprawling factory complex (see below) located just south of the Town Common, McLane and a small army of blacksmiths and carpenters made the highest quality specialized wagons (ambulances, police wagons, and delivery vehicles of every imaginable kind) and sleighs. A self-made man, McLane was also a philanthropist who invested in his town and its people in ways that resonate to this day.

From Pugwash to Park Street

Jared Brown McLane was born in Pugwash, Nova Scotia in 1853—the year North Reading became a town. The youngest of eight children, he left school at an early age to apprentice for a blacksmith and carriage maker. At nineteen, he left Canada and settled in Topsfield, Massachusetts, where he worked for carriage and wagonmaker D.E. Hurd.

Pugwash, Nova Scotia.

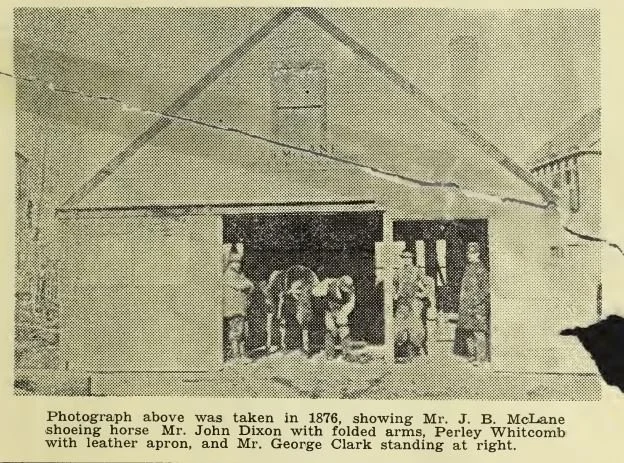

After a few years working in Topsfield, McLane struck out on his own in nearby North Reading, where he bought the blacksmith shop located next to where the Flint Memorial Hall now stands. McLane’s blacksmith business struggled at first, prompting him to undertake several ‘side hustles’: sign painting, road grading, drain building, and snow ‘pathing’ (leveling and flattening snow to allow sleighs to pass more easily - see below).

As his blacksmith business grew (see below), he bought an adjoining building and began building wagons. The Town of North Reading purchased one of the first wagons made by McLane for the use of the local police constable (who also served as fire warden, cattle inspector, and sealer of weights and measures).

McLane’s wagon building enterprise expanded over the following three decades thanks to his capable leadership, marketing nous, and reputation for design innovation and quality construction. McLane’s North Reading factory (pictured below) became one the country’s largest producers of specialty wagons and carriages.

Home and Family

While living in Topsfield, Jared McLane met Alice Long, the daughter of a local blacksmith. McLane’s biography gives us a few hints about what their courtship might have been like. In the winter of 1874-1875, he ran a “dancing school” in the Topsfield town hall, bringing together local youth—including, undoubtedly, his future wife Alice—to socialize and learn to dance. Alice and Jared also served on the board of the local Sons of Temperance (see below) chapter, where he was the treasurer and she led the Women’s Auxiliary. By September 1875, Alice and Jared were married.

The following year, the couple purchased one of North Reading’s finest homes—a sign that the 23 year-old McLane’s business was thriving. His Federal-style home at 148 Park Street (photographed below in 1901) is still standing across the street from the Flint Library. It was built in 1818 by local carpenter Ebenezer Damon, who built several houses around the town common, including the eponymous tavern run by his brother David. Damon built the handsome structure on the foundations of an older house where Jacob Goodwin—one of North Reading’s first doctors—previously lived.

One of the first residents of the new home was Rev. Cyrus Peirce (pronounced ‘purse’)—who came to town in 1819 to assist the North Parish’s octogenarian minister Eliab Stone. A theological liberal, Peirce nudged the parish toward a schism between its Unitarian congregants (like him) and its old-school Trinitarian members. After leaving the parish in 1827 to become a schoolteacher on Nantucket, Peirce went on to establish one of the country’s first teacher training colleges—the Lexington Normal School—which later relocated and evolved into Framingham State University.

In 1828, local physician David Grosvenor bought the home. Over the next five decades, he cared for countless local people there. History remembers Grosvenor as a benefactor of the Center School, located next door to his home, and for a special healing ointment he made out of pumpkin seeds and “checker-berries” (also known as tea berries or wintergreen berries). Following his death (age 91), Grosvenor’s heirs sold the home and adjacent land to the McLanes.

Jared and Alice McLane went on to have two daughters—Lelia (1876-1934) and Bessie (1878-1962). Bessie (pictured below as a high schooler and an adult) was a dynamic, highly intelligent woman who helped found the Kunkshamooshaw Klub, a gathering of local luminaries that hosted monthly evenings of music, poetry, and presentations on a wide range of subjects (women’s suffrage, astronomy, Arctic exploration, to name a few).

Bessie never married and traveled widely in Europe. In 1926, she used her inheritance to build a luxurious Tudor-revival home at the top of Longview Hill in neighboring Reading, where she lived until 1945. A reimagined Cotswolds cottage, 17 Longview Road (seen below) showcased furniture and decorative pieces Bessie acquired on her travels, with each room reflecting a different national theme.

Bessie’s sister Lelia, meanwhile, married Foster Rayner Batchelder, a manager at her father’s factory, who later served as a town Selectman and assistant fire chief. In 1915, they adopted ten-year old Elizabeth (“Betty”), a local girl whose parents had died suddenly within three days of each other. Many years later, Betty and her husband William Doten would live in the McLane house before selling it in 1946 to William Porter, who built a large structure on the property for commercially breeding mink.

Porter’s mink farm struggled, however, and the property was later purchased by the Malden Cooperative Bank, which in 1977 converted the structure into a professional building. Currently, the property is waiting to be redeveloped by its current owner, who plans to preserve and relocate the McLane house away from Park Street, toward the river.

McLane, Massachusetts?

In 1887, Jared McLane began expanding his wagon business by building a factory on the land between his house and the Ipswich River. His industrial footprint steadily grew, helped by the adjacent railway line, which allowed McLane to easily ship his wagons all across the country. The factory employed about fifty local people, including blacksmiths, carpenters, sign painters, and cabinet makers. It primarily built specialized commercial wagons, but also produced smaller carts, sleds, pungs (passenger sleighs), and replacement parts.

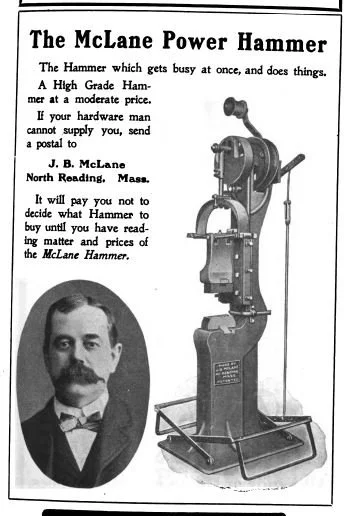

McLane was also an innovator, obtaining four patents for machines he developed for his wagon factory: Axle Cutter (1881); Metal-Punching Machine (1894); Metal-Shearing Machine (1896); and Power Hammer (1902). In 1911, McLane sold the rights to the Power Hammer to Champion Blower and Forge Company, which continued to produce the Power Hammer until 1955.

Click Here to Watch a McLane Power Hammer in Operation (starting at 8m15s)

As well as being a self-made industrial tycoon, McLane was deeply committed to the development and well-being of North Reading and its residents. He was a founding member of the Board of Fire Engineers—the town’s first fire department—and chaired the town’s finance committee for many years. In 1903, McLane helped bring gas street lamps to North Reading, offering to supply lamp posts and fixtures at cost to residents that subscribed to the initiative.

In 1915, he served as State Representative for North Reading, Reading, Woburn, Wilmington, and Burlington. McLane also served on the committee that oversaw the construction of the Batchelder School. It was in this context that McLane made an unorthodox proposal to the people of North Reading. If they voted to rename the town after him, he would donate $10,000 ($310,000 in 2024 dollars) toward the construction of the new school. The town nearly agreed—McLane’s proposal failed by just a few votes. McLane’s gambit was likely inspired by the 1868 decision by the people of South Reading to rename their town in honor of local benefactor and wicker furniture impresario Cyrus Wakefield.

McLane’s Legacy

Jared McLane passed away in 1917, aged 63; his wife Alice died the following year. According to one obituary:

Mr. McLane was a man who kept abreast of the times, and although he was compelled to leave school before reaching the high school, he was considered very well educated by all who knew him. Personal contact with his fellow-men and the newspapers were his principal text books, and he was so well posted on matters pertaining to the affairs of the day that his opinions were eagerly sought and he was considered to be an authority. He was a great student of human nature and very seldom failed in his estimate of men. He possessed an abundance of all-around efficiency and business acumen and inspired confidence in others.

McLane’s son-in-law Foster Batchelder inherited his business, which continued operating (as the North Reading Wagon Factory) until February 1928, when a fire destroyed the entire complex (see below), wrecked several finished wagons, and damaged some nearby businesses. Because of the frigid temperatures, firefighters struggled to pump water from the frozen Ipswich River they needed to put out the fire. The factory folded and was not rebuilt.

Jared McLane helped transform North Reading from a sleepy farming community into a center of manufacturing, innovation, and skilled craftsmanship. Earning good wages, local families prospered, enabling our town to develop and grow. McLane himself played a key role in overseeing and personally funding the development of town infrastructure and public services—especially the town’s schools. Citizens of modern-day North Reading would be wise to emulate Jared McLane’s personal and financial commitment to the common good.