Kunksha-Who-Shaw?

Matthew T. Page shares his original research on the indigenous people of North Reading. After stumbling across documents related to an early 20th century town social club, Matt pulled together a multifaceted story that will transport you back in time.

If you lived in North Reading in the early 1900s, you might have been invited to join the Kunkshamooshaw Klub. Consisting of local luminaries, the Klub hosted monthly evenings of music, poetry, and presentations on a wide range of subjects (women’s suffrage, astronomy, Arctic exploration, to name a few).

Founded in 1901 by Rev. John Hoffman of the Congregational Church, the Kunkshamooshaw Klub was a sophisticated addition to a sleepy town made up of farms, orchards, and cobblers’ workshops. But why give the club such a bizarre name? Who was Kunkshamooshaw?

The 1903-1904 program of the Kunkshamooshaw Klub. Founded in 1901, the club thrived for several years before winding down in 1913. (Gift of the Ryer Family to the NRH&AS)

Explore the full Kunkshamooshaw Klub 1903-1904 Program

The simple answer? David Kunkshamooshaw was one of the last leaders of the indigenous Pawtucket people who—in 1686—relinquished his people’s ancestral claim over thousands of acres of modern-day Essex and eastern Middlesex counties, including areas now known as North Reading. The rest, as they say, is history.

Looking for a more fulsome and interesting answer? Then join us in traveling back in time to the pre-colonial period, when North Reading was blanketed in undisturbed forestlands along the Agawam (now Ipswich) River where the Pawtucket people hunted, fished, and camped for many centuries before European colonists arrived.

Retracing Their Steps

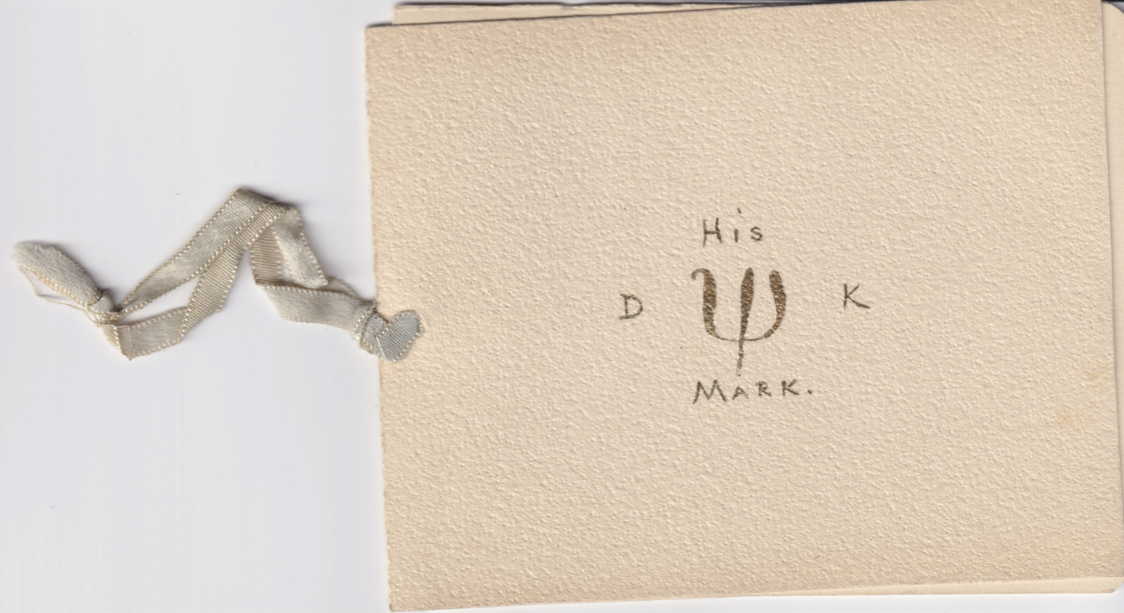

To understand how—and why—David Kunkshamooshaw placed his distinctive bow-and-arrow-shaped mark on the 1686 quit-claim deed (pictured below), we need to understand the story of his people—the Pawtucket—and how they gradually lost control over their native lands. This is their story as much as it is his.

The marks signed by David Kunkshamooshaw (second from left) and other signatories to the Lynn Deed.

Archaeological excavations have shown that the Pawtucket and their ancestors hunted, fished, and built dugout canoes in the upper Agawam River valley and in the area around Martins Pond and the Skug River (an Algonquin name meaning ‘snake’ or ‘black’). Heavily wooded, it was rich with wildlife, including wolves, bears, and even mountain lions. The Pawtucket often temporarily camped at river junctions—places like the confluence of Martins Brook and the Ipswich River near the Park Street bridge or where the Skug flows into Martins Pond near the Oakhaven Sanctuary.

This 1911 photograph of the Ipswich River in North Reading shows how it might have appeared in three centuries earlier. (NRH&AS Collection)

Our town’s landscape was not permanently settled, but was easily accessible from several known Pawtucket villages: Saugus, Cochichewick (in North Andover), Shawshin (in Andover), Shenewemedy (on the west side of Topsfield), Wahquamesecock (on the west side of Danvers), and Naumkeag (in North Beverly), Pentucket (in Haverhill), and Wamesit (near Lowell). The population and location of these settlements waxed, waned, and shifted slightly over the centuries as their inhabitants relocated based on the season, environmental changes, and farming conditions.

Linked by familial and cultural ties to the Pennacook people—a much larger Abenaki cultural grouping whose influence extended into modern-day New Hampshire and beyond—the Pawtucket ranged all along the Merrimack River, its tributaries, and the coast on either side of Cape Ann. Spread across a wide landscape, the Pawtucket consisted of separate bands led by sagamores: chieftains who, advised by tribal elders and with the consent of their kinsfolk, exercised power over specific geographically-defined communal territories. Though the sagamore mantle typically passed from father to son, sometimes a sagamore’s widow would take on her late husband’s leadership role.

At the time the first English colonists began settling in modern-day Essex County in the early 1600s, a single sagamore—Nanepashemet (David Kunkshamooshaw’s great-grandfather)—exercised authority over several Pawtucket-aligned bands spanning what is now northern Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, and southern Maine. At the time, Nanepashemet and his Pawtucket warriors were engaged in an increasingly bitter struggle with Mi'kmaq bands over control of the fur trade in and around southern Maine. In 1619, Mi'kmaq fighters attacked Nanepashemet’s stronghold—a log fort located in modern-day Medford—and killed him. Over the next two decades, the Pawtucket’s feud with the Mi'kmaq would continue, prompting them to cede land to the colonists in return for their protection.

A 1939 diorama imagining how the Pawtucket settlement at the Shattuck Farm site in Andover may have appeared. (Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology)

Arrival and Adaptation

As this struggle over the fur trade suggests, the Pawtucket had contact with Europeans well before the Pilgrims settled at Plymouth. One such example involved a sagamore named Poquanum (also David Kunkshamooshaw’s great-grandfather), who, in 1602, surprised Englishman Bartholomew Gosnold when he wore an English gentleman’s suit to meet the visiting trader when he stopped at Nahant.

In addition to conveying the latest London fashions, trade with Europeans also brought diseases that indigenous peoples’ immune systems were unable to fight. From 1616 to 1619, an epidemic known as “The Great Dying” decimated Pawtucket villages. During the epidemic, up to 50 percent of the indigenous population of the North Shore died, likely from a bacterial infection (leptospirosis) spread by rats and contaminated ballast stones carried aboard European ships.

The Great Dying and Nanepashemet’s death left the Pawtucket reeling. Keen to maintain Pennacook-Pawtucket unity in the face of external threats, tribal leaders agreed that Papisseconnewa—a Pennacook sagamore based at Amoskeag (modern-day Manchester, New Hampshire)—would replace Nanepashemet as their overall leader. Control over Pawtucket territory was initially divided between Nanepashemet’s two eldest sons and his widow, known to history only as the “Squaw Sachem,” saunkskwa (female sagamore) of Mistick (an area encompassing most of modern-day greater Boston).

The Saunkskwa as depicted on the Robbins Memorial Flagstaff in Arlington, Massachusetts

During the 1620s and early 1630s, the Saunkskwa, her sagamore sons, and sagamore Masconomet of the Agawam band allowed colonists to settle in their fur-rich domains, negotiating land grants without entirely surrendering their autonomy or land use rights. For their part, early colonial authorities were keen to maintain good relations with the native population. To this end—and ensure their title claims were legally secure under English law—they typically paid compensation (however meager) to indigenous leaders.

As time went on, however, that willingness to recognize indigenous land claims swiftly diminished as the colonial population grew, encroachment accelerated, more land was turned over to pasture and cultivation, and settler attitudes toward the dwindling native population hardened. The chartering of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628), the subsequent introduction of prejudicial land laws, and the massive influx of 21,000 English colonists during the Great Migration (1630-1640) made early land sharing arrangements untenable.

In 1632 and 1633, another epidemic (smallpox) swept through Pawtucket communities. Up to 90 percent of the indigenous population—including two of Saunkskwa’s and Nanepashemet’s three sons—died in the outbreak. Their youngest son, Wenepaweekin (also known as Sagamore George or George No-Nose) survived but was left disfigured by the disease. He became the sole heir to the Pawtucket lands where several thousand people once lived. Two decades and two epidemics later, just a few hundred remained.

The Beginning of the End

“God hath hereby cleared our title to this place.” Uttered in the wake of the epidemic, this heartless remark by Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop reflected many colonists’ belief that the epidemic was a divine signal that they should assert greater control—both de facto and de jure—over native-owned lands. Over the next two decades, Winthrop and others moved to claim newly “void” native lands: areas that had been depopulated by disease or displacement caused by colonial encroachment. To enable that process, the General Court—the Colony’s legislature—passed new laws curtailing Pawtucket-Pennacook land rights in 1634. To gain land rights, indigenous people had to adopt English culture, religious beliefs, and sedentary farming practices. Such “civilized” natives, it was envisioned, would receive equal treatment under English law.

In reality, however, such equal status was elusive. Depopulation, over-trapping, and disruption of traditional livelihoods upended indigenous economies. The Pawtucket’s few remaining leaders—the Saunkskwa, her son Wenepaweekin, and Masconomet—lacked the financial resources to adequately support themselves and their people.

To do so, they pursued divergent strategies. The Saunkskwa (d. 1650) and Masconomet (d. 1658) sold additional tracts of land for what little they could get and acceded (in 1644) to colonial demands to convert to Christianity and formally recognize English authority, and support the creation of “Praying Towns” where Christianized natives would settle. Wenepaweekin took a riskier approach, tenaciously litigating land claims in the colonial court system and later joining Pometacomet’s attempt to resist colonial rule (better known as King Philip’s War). In the end, none of these strategies were more than stopgaps.

A romanticized painting of Puritan evangelist John Eliot preaching to indigenous peoples.

Indeed, the establishment of Praying Towns from the 1650s onwards essentially finalized the loss of Pawtucket control over their ancestral homelands in what is now Essex and Middlesex counties. Precursors to nineteenth-century Indian reservations, these towns—Natchik (in Natick), Wamesit (in Tewksbury), Hassanamesit (in Grafton), among others)—were promoted as havens of cross-cultural fusion and relative safety from intensifying raids by Mohawk war bands. Led by descendants of prominent sagamores, Praying Towns offered native populations a possible pathway to near-term survival and, perhaps, long-term prosperity.

Seeing Red

This social experiment was soon upended by a war fueled long-simmering tensions between indigenous populations and the ever-expanding colonial population. In 1675, Pometacomet’s Resistance (aka King Philip’s War) erupted, leading to violent clashes between local militias supported by native allies and warriors from the Wampanoag, Nipmuc, and some other tribes. Over the course of the war, fifty-two English towns were attacked, a dozen were destroyed, and more than 2,500 colonists and at least 5,000 Native Americans were killed.

A map showing the approximate location of tribal groupings involved in Pometacomet’s Resistance overlayed on modern state boundaries.

During the war, colonial attitudes toward indigenous people (including, surprisingly, those that remained neutral or fought alongside the English against Pometacomet’s forces) hit rock bottom. Responding to the public hysteria caused by deadly attacks on frontier towns, colonial authorities sold many natives into slavery or moved them into squalid detention camps on Deer Island in Boston Harbor where many died of exposure, starvation, and disease. Vengeful vigilantes attacked Praying Towns, meting out violence against indigenous people who had been forcibly relocated there after the war broke out.

Early on in the war, many Pawtucket still living on the North Shore fled north into Penacook territory to escape the fallout from the fighting. A few—including Wenepaweekin’s close relative James Quonopohit —volunteered to act as scouts and spies for the colonial authorities. Fatefully, Wenepaweekin himself opted to side with Pometacomet against the English. After the war, he was arrested and sold into slavery in Barbados. James later succeeded in repatriating Wenepaweekin, bringing him back to live out his remaining years in Natick.

Survival Strategies

Following Pometacomet’s defeat, colonial authorities ramped up their efforts to contain indigenous populations and seize their lands. In 1677, the General Court ordered all natives to live in the few remaining Praying Towns. English overseers replaced sovereign tribal governance bodies and courts increasingly treated natives much less equitably than before the war. In 1679, the leaders of the New England colonies met to divide up most of the region’s remaining native lands, paying little heed to whether particular tribes fought for or against them during the war. Large tracts of native land were declared “vacant,” clearing the way for their settlement by land-hungry colonists.

With the writing on the wall, the few Pawtucket families still living in what is now Massachusetts faced stark choices about their own survival. Some fled norththrough the White Mountains to Abenaki settlements and Catholic missions along the St. Lawrence River, fighting with the French against the English in later colonial wars. Today, some Pawtucket descendants live at Odanak, in Quebec. Others stayed in the Praying Towns, whose population dwindled from 212 in 1678 to just 37 in 1763. Some were eradicated in the early 18th century, when Massachusetts authorities periodically paid bounties on the scalps of indigenous men, women, and children. As a people, the Pawtucket no longer exist today, though their descendants belong to other tribes present in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Canada.

But what became of the descendants of Nanepashemet, the once mighty sagamore of the Pawtucket-Pennacook alliance whose ancestral homelands included modern-day North Reading? After his youngest son and heir Wenepaweekin died a broken man in 1684, he passed on his land claims to his relative James Quonopohit, his daughter Cecily, and his grandson David Kunkshamooshaw. Having gained no traction during his lifetime, these claims soon became more relevant in 1686 when King James II revoked the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s charter and established the royal Dominion of New England.

Upon his arrival in Massachusetts, the Dominion’s royal governor Edmund Andros (pictured below) quickly questioned the validity of the colony’s land law and its reliance on titles purchased from native leaders like the Saunkskwa and Masconomet. Andros refused to recognize any title that did not originate from the King, claiming royal ownership via the ‘right of discovery’. He demanded that all land-holding colonists had to apply for new titles in exchange for a fee based on the size of their holdings.

According to Andros, a native’s signature on a land title had “no more worth than a scratch with a bear’s paw.” Andros’ edict created confusion around the legal validity of existing colonial deeds signed by natives. Sensing an opportunity, indigenous claimants like James Quonopohit reasserted claims that had been long-ignored in the hope that they could obtain some degree of compensation for lands that had been taken from their forebears. For their part, colonists saw an opportunity to reconsecrate the validity of their titles, thus putting pressure on Andros to recognize them. Amid the legal and political tumult of the mid-to-late 1680s, these strategies largely worked.

This said, the new quit-claim deeds like the one signed by James Quonopohit, David Kunkshamooshaw et al. did not adequately compensate them or their people for being dispossessed of their ancestral homelands over the foregoing decades. In exchange for their claim over the towns of Lynn, Lynnfield, Nahant, Saugus, Swampscott, and Reading (consisting of modern-day Wakefield, North Reading, and Reading), they received just sixteen pounds sterling (worth about $5,000 today): scant compensation for their land or near-extinction of the Pawtucket people.

Kunkshamooshaw’s Legacy

It is unclear if the North Reading residents who named their social club after David Kunkshamooshaw really understood the story of his Pawtucket people. They may have seen him more of a mascot or a romanticized ideal, rather than one of the last survivors of the indigenous people of our town. Or, by adopting his long-forgotten name, they may have been quietly acknowledging—for the first time—that he and his Pawtucket people had value and were worth remembering.

The Kunkshamooshaw Klub programs donated to the North Reading Historical & Antiquarian Society by the Ryer family reveal that its members—the Rev. Hoffman, Bessie McLane, among many others—were romantics and aspiring intellectuals keen to deepen their understanding of the world. And unlike David Kunkshamooshaw, they had the freedom, resources, and safety to self-actualize, rather than simply fight to survive.

Having deepened our understanding of David and his people, perhaps it is fitting that we conclude this article by asking the same (rhetorical) question discussed by Kunkshamooshaw Klub members at their meeting on April 1st, 1910, pictured below:

“Should Kunkshamooshaw be forgot?”

Want to learn more about the Pawtucket people? Here is some further reading: